Did Jesus drink alcohol? Should Christians drink alcohol?

Christianity.com: Did Jesus drink alcohol? Should Christians drink alcohol?-Brian Hedges from christianitydotcom2 on GodTube.

Saint Augustine on Rightly Ordered Love

|

| St. Augustine by Sandro Botticelli |

In his City of God, Saint Augustine defined

virtue as “rightly ordered love” (City of

God, XV.23). The right ordering of love was a running theme in Augustine’s

life and writings. In one of his clearest explanations, he said:

But living a just and holy life requires one to be capable of an

objective and impartial evaluation of things: to love things, that is to say,

in the right order, so that you do not love what is not to be loved, or fail to

love what is to be loved, or have a greater love for what should be loved less,

or an equal love for things that should be loved less or more, or a lesser or

greater love for things that should be loved equally. (On Christian Doctrine, I.27-28)

Augustine’s conception of

rightly ordered loves has prompted a lot of substantial and creative theological reflection over the

centuries. In Purgatorio, for

example, Dante conceived of the seven deadly sins in terms of disordered love.

The proud, envious and wrathful were guilty of misdirected love; the slothful were guilty of deficient love; and the avaricious, gluttonous, and

lustful were guilty of excessive

love. While I don’t believe in purgatory, these characterizations of sin in

relationship to love are still helpful. If virtue is love rightly ordered in

our hearts, it stands to reason that vice is the opposite.

This understanding of

virtue and vice meshes with Scripture’s insistence that love is the fulfillment

of the law (Rom 13:8; Gal 5:14; James 2:8). Augustine called virtues “the

various movements of love,” and described the four cardinal virtues in terms of love:

I

hold that virtue is nothing other than perfect love of God. Now, when it is

said that virtue has a fourfold division, as I understand it, this is said

according to the various movements of love…We may, therefore, define these

virtues as follows: temperance is love preserving itself entire and incorrupt

for God; courage is love readily bearing all things for the sake of God;

justice is love serving only God, and therefore ruling well everything else

that is subject to the human person; prudence is love discerning well between

what helps it toward God and what hinders it. (On the Morals of the Catholic Church, XV.25)

Beneath Augustine’s

conception of virtue as rightly ordered love was a foundational conviction

about the nature of reality. Augustine believed that the summum bonum, the highest good, was God

himself and that all other goods are lesser goods that flow from his hand, intended to lead us back to him. In the Confessions,

for example, Augustine says:

For

there is a joy that is not given to those who do not love you, but only to

those who love you for your own sake. You yourself are their joy. Happiness is

to rejoice in you and for you and because of you. This is happiness and there

is no other. Those who think that there is another kind of happiness look for

joy elsewhere, but theirs is not true joy. (Confessions,

X.22)

Within this framework, sin springs from hearts that neglect God as the Supreme Good

and seek their happiness in lesser goods. But such people ignore the order and

nature of reality. This is the heart of evil: to prefer a lesser good

over the Supreme Good, to worship and serve the creature rather the Creator

(Rom 1:25).

These

are thy gifts; they are good, for thou in thy

goodness has made them.

Nothing

in them is from us, save for sin when,

neglectful of order,

We

fix our love on the creature, instead of on thee,

the Creator.

(City

of God, XV.22)

Augustine’s ethical system

is an outgrowth of this conviction. Echoes of this are everywhere in his

writings. Commenting on one of the Psalms, he writes:

He who made all said, Ask what thou wilt: yet nothing wilt thou find

more precious, nothing wilt thou find better, than Himself who made all things.

Him seek, who made all things, and in Him and from Him shalt thou have all

things which He made. All things are precious, because all are beautiful; but

what more beautiful than He? Strong are they; but what stronger than He? And

nothing would He give thee rather than Himself. If aught better thou hast

found, ask it. If thou ask aught else, thou wilt do wrong to Him, and harm to

thyself, by preferring to Him that which He made, when He would give to thee

Himself who made. (Commentary on the Psalms,

Psalm 35.9, in NPNF, 1.8.81)

I’m sure that I have not done

justice to Augustine’s theology of love and ethics. A lifetime could be devoted

to exploring this theme in Augustine! Nevertheless, I think Augustine’s

understanding of sin in relationship to love, and love in relationship to the

hierarchy of goods, helps us in at least four ways:

1. First of all, it

tightly tethers our thinking about ethics to the heart. Behavior matters, but

behavior is always a reflection of what’s going on in the heart – of what we

love. This means that we can never settle for mere outward compliance with

rules. Our approach to spiritual transformation must

always be inside out. If we would change our ways, we must first order our

loves.

2. Augustine’s approach allows us to embrace all created goods in

their proper order. Other goods do not need to be rejected, but rather submitted, put in order, held in their proper place. Consider, for example, how Augustine discusses the good of

physical beauty:

Now

physical beauty, to be sure, is a good created by God, but it is a temporal

good, very low in the scale of goods; and if it is loved in preference to God,

the eternal, internal, and sempiternal Good, that love is as wrong as the

miser’s love for gold, with the abandonment of justice, though the fault is in

the man, not in the gold. This is true of everything created; though it is

good, it can be loved in the right way or in the wrong way – in the right way,

that is, when the proper order is kept, in the wrong way when that order is

upset. (City of God, XV.22)

3. Thirdly, this means that one of our aims in Christian living should be

learning to love and enjoy God through the things he has made. This is the only

way to avoid idolatry. If we allow our love to terminate on a lesser good, our

love for it becomes ultimate and therefore central. In Augustine’s own words, “He loves Thee too little who loves

anything together with Thee, which he loves not for Thy sake.” (Confessions, X.29)

So, how do we learn this?

How do we enjoy a created thing without making it an idol? How do we, to use a

phrase from C. S. Lewis, chase the sunbeam back up to the sun?

I think the answer is that

we must trace the specific features of the things we enjoy back to their source

in God. Created goods are temporal, finite streams that flow to us from the

fountain of God’s uncreated and unending goodness. “Every good gift and every

perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights with whom

there is no variation or shadow due to change” (James 1:17).

So when you enjoy the

taste of food, remember that the Creator of food is Christ himself, the Bread

of Life, and then taste and see that he is good. When you are mesmerized by the

enchanting sound of music, remember that this is but an echo of the original

Voice, whose love song birthed creation.

Tell me. Love, if thou canst, anything which He hath not made. Look

round upon the whole creation, see whether in any place thou art held with the

birdlime of desire, and hindered from loving the Creator, except it be by that

very thing which He hath Himself created, whom thou despisest. But why dost

thou love those things, except because they are beautiful? Can they be as

beautiful as He by whom they were made? Thou admirest these things, because

thou seest not Him: but through those things which thou admirest, love Him whom

thou seest not. (Commentary on the Psalms,

on Psalm 80:11 in NPNF, 1.8.389)

4. Finally, Augustine's writings constantly remind us that learning to love God

in everything is a work of grace. We cannot order our own hearts.

That’s why every sentence in Augustine’s Confessions

is a prayer. He had learned first hand how absolutely dependent he was on

God’s grace. That’s why he prayed,

O

Love ever burning, never quenched! O Charity, my God, set me on fire with your

love! You command me to be continent. Give me the grace to do as you command,

and command me to do what you will! (Confessions,

X.29).

And that’s why we also must

pray with Augustine, “Set love in order in me.” (City of God, XV.22).

Prepare Your Public Prayers: Helpful Advice from D. A. Carson

D. A. Carson's helpful advice for people who lead in public prayer:

"If you are in any form of spiritual leadership, work at your public prayers. It does not matter whether the form of spiritual leadership you exercise is the teaching of a Sunday school class, pastoral ministry, small-group evangelism, or anything else: if at any point you pray in public as a leader, then work at your public prayers.

Some people think this advice distinctly corrupt. It smells too much of public relations, of concern for public image. After all, whether we are praying in private or in public, we are praying to God: Surely he is the one we should be thinking about, no one else.

This objection misses the point. Certainly if we must choose between trying to please God in prayer, and trying to please our fellow creatures, we must unhesitatingly opt for the former. But that is not the issue. It is not a question of pleasing our human hearers, but of instructing them and edifying them.

The ultimate sanction for this approach is none less than Jesus himself. At the tomb of Lazarus, after the stone has been removed, Jesus looks to heaven and prays, “Father, I thank you that you have heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I said this for the benefit of the people standing here, that they may believe that you sent me” (John 11:41-42). Here, then, is a prayer of Jesus himself that is shaped in part by his awareness of what his human hearers need to hear.

The point is that although public prayer is addressed to God, it is addressed to God while others are overhearing it. Of course, if the one who is praying is more concerned to impress these human hearers than to pray to God, then rank hypocrisy takes over. That is why Jesus so roundly condemns much of the public praying of his day and insists on the primacy of private prayer (Matt. 6:5-8). But that does not mean that there is no place at all for public prayer. Rather, it means that public prayer ought to be the overflow of one’s private praying. And then, judging by the example of Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus, there is ample reason to reflect on just what my prayer, rightly directed to God, is saying to the people who hear me.

In brief, public praying is a pedagogical opportunity. It provides the one who is praying with an opportunity to instruct or encourage or edify all who hear the prayer. In liturgical churches, many of the prayers are well-crafted, but to some ears they lack spontaneity. In nonliturgical churches, many of the prayers are so predictable that they are scarcely any more spontaneous than written prayers, and most of them are not nearly as well-crafted. The answer to both situations is to provide more prayers that are carefully and freshly prepared. That does not necessarily mean writing them out verbatim (though that can be a good thing to do). At the least, it means thinking through in advance and in some detail just where the prayer is going, preparing, perhaps, some notes, and memorizing them.

Public praying is a responsibility as well as a privilege. In the last century, the great English preacher Charles Spurgeon did not mind sharing his pulpit: others sometimes preached in his home church even when he was present. But when he came to the “pastoral prayer,” if he was present, he reserved that part of the service for himself. This decision did not arise out of any priestly conviction that his prayers were more efficacious than those of others. Rather, it arose from his love for his people, his high view of prayer, his conviction that public praying should not only intercede with God but also instruct and edify and encourage the saints.

Many facets of Christian discipleship, not least prayer, are rather more effectively passed on by modeling than by formal teaching. Good praying is more easily caught than taught. If it is right to say that we should choose models from whom we can learn, then the obverse truth is that we ourselves become responsible to become models for others. So whether you are leading a service or family prayers, whether you are praying in a small-group Bible study or at a convention, work at your public prayers."

What To Do When You Are Tempted

How do you handle temptation?

I’m not talking about the fleeting, seemingly benign thought of sin that may hold initial allure, but is easily dismissed. (Though we should be on guard against these kinds of thoughts, too).

No, I’m talking about that moment when you’ve savored the juicy morsel and like the taste. You clamp down your jaws and suddenly feel the sharp piercing desire for more and a forceful tug towards deliberate, willful sin. You realize that you’ve swallowed a hook and the angler is reeling you in. Your better judgment, and God’s Word, and the Holy Spirit are whispering “No.” But your appetites and emotions are screaming, “Yes!”

I have in mind those times when you are like Peter in the courtyard, your heart frenzied by fear, about to commit an act of cowardice and treachery. Or David on the rooftop, seized by lust’s hot desire, teetering on the brink of adultery. Or Moses at the rock, boiling in anger, poised to open a valve that will erupt into a rebellious torrent of volcanic rage.

Can you still escape temptation when you’re in that deep?

The great 17th century pastor and theologian, John Owen, thought so. In his incisive and insightful book on temptation, Owen provides both analysis and diagnosis for tempted souls, with directions for watching and praying in order to avoid temptation. But, wise soul physician that he was, Owen also offered counsel to the person already in temptation’s tenacious grip.

Suppose the soul has been surprised by temptation, and entangled at unawares, so that now it is too late to resist the first entrances of it. What shall such a soul do that it be not plunged into it, and carried away with the power thereof?[i]

He counsels four things that I find both helpful and hopeful but will phrase in mostly my own words.

(1) Pray. Ask the Lord for help.

You’re about to sink under the waves. The water is to your neck. You’re gasping for air, but gulping mouthfuls of water. Your breath is gone. You’re about to go under. What do you do? Cry out with Peter, “Lord, save me!” Jesus will stretch out his hand and catch you (Matthew 14:30-31).

This is the first and most immediate step. Pray.

Stop and do it now.

(2) Run to Jesus, who has already conquered temptation in your place.

Running to Jesus is, of course, what we do when we pray. But when you are strongly tempted, don’t just turn to Jesus in general. Run to him for specific, tangible help, remembering that he has already conquered temptation in your place.

For because he himself has suffered when tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted…. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin. Let us then with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need (Hebrews 2:18; 4:15-16)

Remember this: Jesus was tempted, not first and foremost as our example, but as our brother, captain, and king. Adam, our first representative, was tempted in paradise and failed. Jesus, the Second Adam and our final representative, was tempted in the desert and conquered. As our hero and champion, Christ has already defeated and beheaded Goliath. He has crushed the serpent’s head. The battle is already won.

So run, weary Christian. Run to your conquering King!

(3) Expect the Lord to give deliverance.

This is his promise. “No temptation has overtaken you that is not common to man. God is faithful, and he will not let you be tempted beyond your ability, but with the temptation he will also provide the way of escape, that you may be able to endure it” (1 Corinthians 10:13). Expect him to fulfill it.

And keep in mind that the Lord has many ways of delivering you. He may send an affliction or a trial that takes the edge off your appetite for sin and restores your hunger for his Word. “Before I was afflicted I went astray, but now I keep your word” (Psalm 119:67).

He may give you sufficient grace to endure the temptation (2 Corinthians 12:8-9; James 1:12). He may rebuke the enemy, so that he flees from you (Zechariah 3:1-2; James 4:7). Or he may revive you with some refreshing comfort from his Spirit and encouragement from his Word.

But be sure of this: the Lord has more ways to deliver than Satan has ways to tempt. “Greater is he that is in you, than he that is in the world” (1 John 4:4b, KJV).

(4) Repair the breach and get back on the right path.

Finally, after you’ve found some immediate relief from the Lord, repair the breach and get back on the happy, narrow road of righteousness.

C. S. Lewis said, “A sum can be put right: but only by going back till you find the error and working it afresh from that point, never by simply going on. Evil can be undone, but it cannot ‘develop’ into good. Time does not heal it.”[ii]

It is important, then, to figure out why and how we entered into temptation in the first place. Big sins always follow little sins. Sins of commission usually follow sins of neglect. When you have found yourself unusually tempted, follow the trail back. You will probably find carelessness, prayerlessness, and neglect.

Ask the Lord to search you and know your heart, to try you and know your thoughts, to see if there is any grievous way in you and to lead you in the way everlasting (Psalm 139:23-34).

But be careful even in your repentance. Don’t become obsessed with turning from temptation and sin; focus on turning to Christ. In the wise words of Jack Miller, “When you turn to Christ, you don’t have a repentance apart from Christ you just have Christ. Therefore don’t seek repentance or faith as such but seek Christ. When you have Christ you have repentance and faith. Beware of seeking an experience of repentance; just seek an experience of Christ.”[iii]

Christ is the one who both preserves the tempted and restores the fallen (Luke 22:21-22; John 21). So, wherever you are in respect to temptation and sin, seek Christ.

This post was written for Christianity.com.

Notes

[i]John Owen, Overcoming Sin and Temptation, edited by Justin Taylor and Kelly Kapic (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2006) p. 207.

[ii]C. S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (New York, NY: HarperOne, 1946, 1973) p. viii.

[iii] John C. Miller, The Heart of a Servant Leader: Letters from Jack Miller (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2004), p. 244.

Bodies Matter

|

| Auguste Rodin's The Thinker |

As pastors, we often think of ourselves as spiritual

practitioners – “physicians of the soul.” And so we are. We are charged with

keeping watch over the souls of our people (Heb. 13:17). And we are ministers

of the new covenant, ministers of the Spirit (2 Corinthians 3).

But we must beware of forgetting that all human spirituality

is by necessity embodied spirituality.

We are physical, earth-bound creatures and all of our relating to God, Christ,

the Spirit, the Word, and one another is defined by our physicality.

To treat

people as if they are bodiless souls is to be one step removed from the reality

in which they live. People have bodies and their bodies matter.

This is a good thing. God created us with bodies and

said that they (along with everything else he created) were very good (Gen.

1:31). The doctrine of creation reminds us of the goodness of the physical.

But

even more amazing is the fact that Word by whom all things were created (John

1:3) became flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14). God took on a body! “A body

you have prepared for me,” Jesus said (Heb. 10:5).

Christian orthodoxy has

always held that the body of Jesus was a real body, not a phantom body (as was

taught in the old heresy of Docetism); furthermore, that he rose again,

ascended and was exalted in this very real human body. So the doctrines of

incarnation and resurrection join the doctrine of creation in reminding us of

the intrinsic value and importance of the body.

It is no wonder then that the New Testament places such

importance on the body.

- Paul

prayed for the sanctification of the body: “Now may the God of peace

himself sanctify you completely, and may your whole spirit and soul and

body be kept blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Thess.

5:23, ESV).

- James

warned us that goodwill which fails to minister to bodily needs is nothing more than dead faith: “If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and

lacking in daily food, and one of

you says to them, ‘Go in peace, be warmed and filled,’ without giving them

the things needed for the body, what good is that? So also faith by itself, if it does not

have works, is dead” (James 2:15-17, ESV).

- We are

exhorted to flee sexual immorality precisely because it is a sin committed

against the body – the body which is God’s temple, God’s gift, and God’s

purchase: “Flee from sexual immorality. Every other sin a person commits

is outside the body, but the sexually immoral person sins against his own

body. Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit

within you, whom you have from God? You are not your own, for you were

bought with a price. So glorify God in your body” (1 Cor. 6:18-20).

- Paul

further teaches that we will “all appear before the judgment seat of

Christ, so that each one may receive what is due for what he has done in

the body, whether good or evil” (2 Cor. 5:10, ESV).

- And our

great Christian hope is that someday Christ “will transform our lowly body

to be like his glorious body” (Philip. 3:21, ESV) and that “this

perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must

put on immortality” (1 Cor. 15:53, ESV).

Is it any wonder then that we are exhorted “by the mercies

of God, to present [our] bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to

God, which is [our] spiritual worship” (Rom. 12:1, ESV)?

The conclusion of all this is that people’s bodies matter. We must minister to our congregants as embodied souls, remembering that they (like we) are but dust (Psalm

103:14) with flesh that is weak (Matt. 26:41).

We must remember that they physical needs as well as spiritual needs. And we must beware of

implicitly teaching the Gnostic error that the body is evil.

Instead, let’s remind people that our bodies, though fallen,

are gifts of our good and wise Creator God who has revealed His glory in the

body of Jesus Christ and has promised to not only save our souls but also to

raise our bodies in glory; therefore we should use our bodies for

thankful worship and sanctified service to him.

Making It Personal

- Do I

take into account the fact that human beings are inescapably physical

beings, and that this is a good thing?

- Is my

ministry marked by an appropriate concern and compassion for people’s

physical needs (food, clothing, health) as well as their spiritual needs?

- Do the

great doctrines of creation, incarnation, and resurrection have due impact

on the way I think of the body?

- Have I

unconsciously taught people that the body is evil or that physical things

are unimportant?

This article was originally published by Life Action Ministries for Pastor Connect.

For a helpful book length treatment of human physicality from a Christian perspective, check out Matthew Lee Anderson's Earthen Vessels: Why Our Bodies Matter to Our Faith.

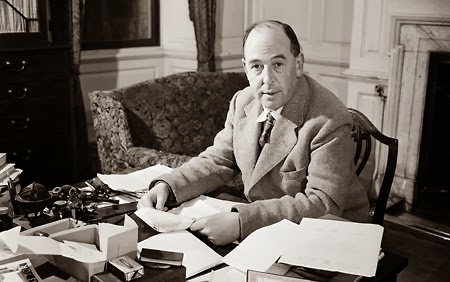

C. S. Lewis on the True Source of Happiness

|

| C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) |

"All joy (as distinct from mere pleasure, still more amusement)

emphasizes our pilgrim status: always reminds, beckons, awakens desire. Our

best havings are wantings."

--Letters of C. S. Lewis, p.

441

"God gives what He has, not what He has not: He gives the happiness

that there is, not the happiness that is not. To be God - to be like God and to

share His goodness in creaturely response - to be miserable - these are the

only three alternatives. If we will not learn to eat the only food that the

universe grows - the only food that any possible universe can ever grow - then

we must starve eternally."

--The Problem of Pain, p.

47

“What Satan put into the heads of our remote ancestors was the idea that

they could 'be like gods' - could set up on their own as if they had created

themselves - be their own masters - invent some sort of happiness for

themselves outside God, apart from God. And out of that hopeless attempt has

come nearly all that we call human history - money, poverty, ambition, war,

prostitution, classes, empires, slavery - the long terrible story of man trying

to find something other than God which will make him happy. The reason why it

can never succeed is this. God made us: invented us as a man invents a machine.

A car is made to run on petrol, and it would not run properly on anything else.

Now God designed the human race to run on Himself. He Himself is the fuel our

spirits were designed to burn, or the food our spirits were designed to feed

on. There is no other. That is why it is just no good asking God to make us

happy in our own way without bothering about religion. God cannot give us

happiness and peace apart from Himself, because it is not there. There is no

such thing.”

--Mere Christianity, p. 50

“I think one may be quite rid of the old haunting suspicion—which raises

its head in every temptation—that there is something else than God, some other

country into which he forbids us to trespass, some kind of delight which he

‘doesn’t appreciate’ or just chooses to forbid, but which would be real delight

if only we were allowed to get it. The thing just isn’t there. Whatever

we desire is either what God is trying to give us as quickly as he can, or else

a false picture of what he is trying to give us, a false picture which would

not attract us for a moment if we saw the real thing. . . . He knows what we

want, even in our vilest acts. He is longing to give it to us. . . .The truth

is that evil is not a real thing at all, like God. It is simply good spoiled.

. . . You know what the biologists mean by a parasite—an animal that lives on

another animal. Evil is a parasite. It is there only because good is

there for it to spoil and confuse.”

--They Stand Together: The Letters of C. S. Lewis to Arthur Greeves

(1914-1963), p. 465. Italics original.

“The New Testament has lots to say about self-denial, but not about

self-denial as an end in itself. We are told to deny ourselves and to take up

our crosses in order that we may follow Christ; and nearly every description of

what we shall ultimately find if we do contains an appeal to desire. If there

lurks in most modern minds the notion that to desire our own good and earnestly

to hope for the enjoyment of it is a bad thing, I submit that this notion has

crept in from Kant and the Stoics and is no part of the Christian faith. Indeed,

if we consider the unblushing promises of reward and the staggering nature of

the rewards promised in the Gospels, it would seem that Our Lord finds our

desires not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling

about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an

ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot

imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too

easily pleased!”

--The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses, p. 25-26.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)